Mapping cone (homological algebra)

In homological algebra, the mapping cone is a construction on a map of chain complexes inspired by the analogous construction in topology. In the theory of triangulated categories it is a kind of combined kernel and cokernel: if the chain complexes take their terms in an abelian category, so that we can talk about cohomology, then the cone of a map f being acyclic means that the map is a quasi-isomorphism; if we pass to the derived category of complexes, this means that f is an isomorphism there, which recalls the familiar property of maps of groups, modules over a ring, or elements of an arbitrary abelian category that if the kernel and cokernel both vanish, then the map is an isomorphism. If we are working in a t-category, then in fact the cone furnishes both the kernel and cokernel of maps between objects of its core.

Contents |

Definition

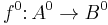

The cone may be defined in the category of chain complexes over any additive category (i.e., a category whose morphisms form abelian groups and in which we may construct a direct sum of any two objects). Let  be two complexes, with differentials

be two complexes, with differentials  i.e.,

i.e.,

and likewise for

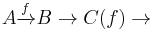

For a map of complexes  we define the cone, often denoted by

we define the cone, often denoted by  or

or  to be the following complex:

to be the following complex:

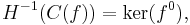

![C(f) = A[1] \oplus B = \dots \to A^n \oplus B^{n - 1} \to A^{n %2B 1} \oplus B^n \to A^{n %2B 2} \oplus B^{n %2B 1} \to \cdots](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/aebb774872fae12d7e2ba23b376a5731.png) on terms,

on terms,

with differential

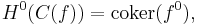

![d_{C(f)} = \begin{pmatrix} d_{A[1]} & 0 \\ f[1] & d_B \end{pmatrix}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2939b319edb09a6cb4ba436a4b002f8d.png) (acting as though on column vectors).

(acting as though on column vectors).

Here ![A[1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4c91b246bb2d1dadc430ab7ac1affa99.png) is the complex with

is the complex with ![A[1]^n=A^{n %2B 1}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/335e42ea73c097801b0ad84022ec5839.png) and

and ![d^n_{A[1]}=-d^{n %2B 1}_{A}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/330b683b1efc19b172eef2e602c19a83.png) . Note that the differential on

. Note that the differential on  is different from the natural differential on

is different from the natural differential on ![A[1] \oplus B](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4cdca205c2ca492f580dca2c20ba89b1.png) , and that some authors use a different sign convention.

, and that some authors use a different sign convention.

Thus, if for example our complexes are of abelian groups, the differential would act as

Properties

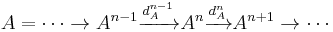

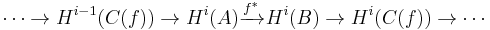

Suppose now that we are working over an abelian category, so that the cohomology of a complex is defined. The main use of the cone is to identify quasi-isomorphisms: if the cone is acyclic, then the map is a quasi-isomorphism. To see this, we use the existence of a triangle

where the maps ![B \to C(f), C(f) \to A[1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8387cc9b477908a445a69ab271f43469.png) are the projections onto the direct summands (see Homotopy category of chain complexes). Since this is a triangle, it gives rise to a long exact sequence on cohomology groups:

are the projections onto the direct summands (see Homotopy category of chain complexes). Since this is a triangle, it gives rise to a long exact sequence on cohomology groups:

and if  is acyclic then by definition, the outer terms above are zero. Since the sequence is exact, this means that

is acyclic then by definition, the outer terms above are zero. Since the sequence is exact, this means that  induces an isomorphism on all cohomology groups, and hence (again by definition) is a quasi-isomorphism.

induces an isomorphism on all cohomology groups, and hence (again by definition) is a quasi-isomorphism.

This fact recalls the usual alternative characterization of isomorphisms in an abelian category as those maps whose kernel and cokernel both vanish. This appearance of a cone as a combined kernel and cokernel is not accidental; in fact, under certain circumstances the cone literally embodies both. Say for example that we are working over an abelian category and  have only one nonzero term in degree 0:

have only one nonzero term in degree 0:

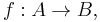

and therefore  is just

is just  (as a map of objects of the underlying abelian category). Then the cone is just

(as a map of objects of the underlying abelian category). Then the cone is just

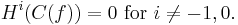

(Underset text indicates the degree of each term.) The cohomology of this complex is then

This is not an accident and in fact occurs in every t-category.

Mapping cylinder

A related notion is the mapping cylinder: let f: A → B be a morphism of complexes, let further g : Cone(f)[-1] → A be the natural map. The mapping cylinder of f is by definition the mapping cone of g.

Topological inspiration

This complex is called the cone in analogy to the mapping cone of a continuous map of topological spaces  : the complex of singular chains of the topological cone

: the complex of singular chains of the topological cone  is homotopy equivalent to the cone (in the chain-complex-sense) of the induced map of singular chains of X to Y. The mapping cylinder of a map of complexes is similarly related to the mapping cylinder of continuous maps.

is homotopy equivalent to the cone (in the chain-complex-sense) of the induced map of singular chains of X to Y. The mapping cylinder of a map of complexes is similarly related to the mapping cylinder of continuous maps.

References

- Manin, Yuri Ivanovich; Gelfand, Sergei I. (2003), Methods of Homological Algebra, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-43583-9

- Weibel, Charles A. (1994), An introduction to homological algebra, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 38, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55987-4, OCLC 36131259, MR1269324

![\begin{array}{ccl}

d^n_{C(f)}(a^{n %2B 1}, b^n) &=& \begin{pmatrix} d^n_{A[1]} & 0 \\ f[1]^n & d^n_B \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} a^{n %2B 1} \\ b^n \end{pmatrix} \\

&=& \begin{pmatrix} - d^{n %2B 1}_A & 0 \\ f^{n %2B 1} & d^n_B \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} a^{n %2B 1} \\ b^n \end{pmatrix} \\

&=& \begin{pmatrix} - d^{n %2B 1}_A (a^{n %2B 1}) \\ f^{n %2B 1}(a^{n %2B 1}) %2B d^n_B(b^n) \end{pmatrix}\\

&=& \left(- d^{n %2B 1}_A (a^{n %2B 1}), f^{n %2B 1}(a^{n %2B 1}) %2B d^n_B(b^n)\right).

\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8d6379ca86d05a582821bdf0494b1af3.png)

![C(f) = \dots \to 0 \to \underset{[-1]}{A^0} \xrightarrow{f^0} \underset{[0]}{B^0} \to 0 \to \cdots.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/152be6b13df8d75f5418733f54e6be4a.png)